TIMELINE (Last updated 23 December 2024)

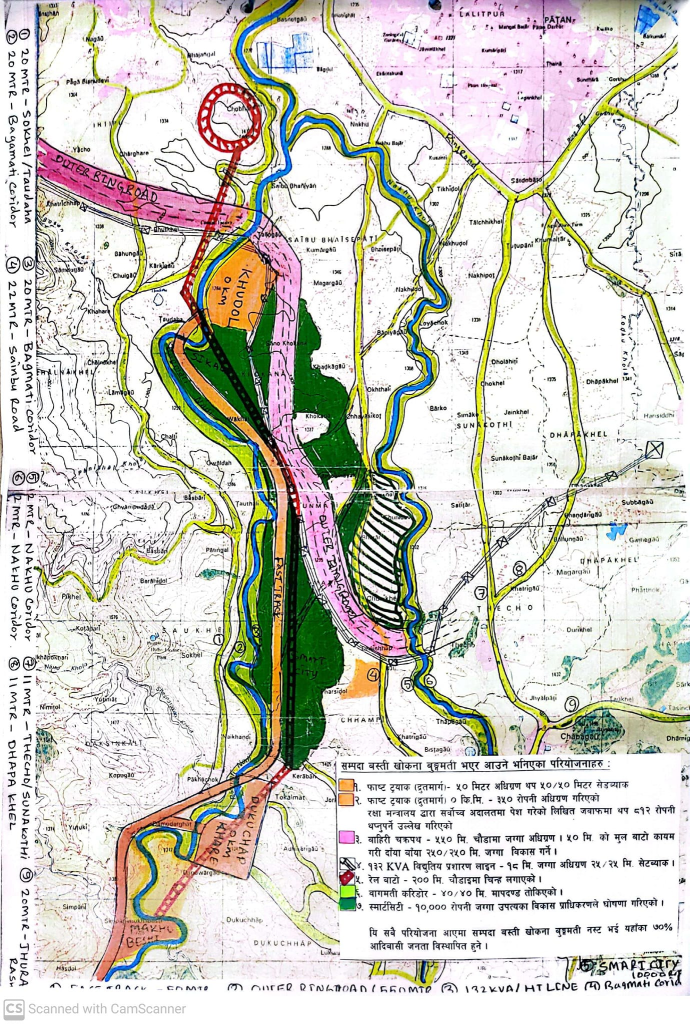

Multiple infrastructure projects pose serious threats of displacement of the Indigenous Newa[1] communities from their lands in historical settlements of Khokana and Bungamati in Lalitpur in the south of Nepal’s capital city of Kathmandu. Primary among those projects is the under-construction Kathmandu-Terai/Madhesh Fast Track (Expressway) Project[2], which is a mega highway project considered as “a project of national pride”. The Expressway, whose feasibility was supported by the Asian Development Bank (ADB)[3], runs along the Bagmati River and is expected to cut the travel distance from the capital Kathmandu to the south of the country by around 160 km as per existing roads. Some 6km of the Expressway will slice through farmlands, communal lands and trust (Guthi) lands as well as ritual routes and sites of Indigenous Newa communities of Khokana and Bungamati.[4] Entry point of the Expressway is planned in Khokana.

Besides the Fast Track, Kathmandu Outer Ring Road[5], Bagmati River Basin Improvement Project[6] and Thankot-Bhaktapur Transmission Line Project[7] under Rural Electrification, Distribution and Transmission Project[8] are other infrastructure projects, which are on or around the proposed alignment of the Expressway and impact the communities in Khokana and Bungamati. The latter two are also ADB-financed projects. The Transmission Line Project is now listed as “closed” on the ADB website while the transmission towers planned in Khokana under the project were long stalled and could not be erected due to community resistance – few towers that were forcibly erected remain without wires.[9]

Further, one of the four new or “Smart Cities” planned in Kathmandu valley[10] is also proposed in and around Khokana and Bungamati over an area of 10,000 ropanis[11]. The Satellite Cities and Outer Ring Road are reportedly being supported by Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA).[12] Further, there are also reports of Nepal-India Railway line[13] and petroleum pipeline and storage facility proposed or planned along the Fast Track or near its entry point. All those projects together will displace the Newa communities of Khokana and Bungamati entirely. That is why the affected communities have constantly rejected the Fast Track and other harmful projects on their lands and not allowed the construction of the Fast Track in the area so far. Below is the timeline of key events in relation to the communities’ campaigns.

Picture credit: Nepali Times/Sahina Shrestha

Picture credit: The Record/Supriya Manandhar

1950s – early 2000s

The trade route between Nepal and India has been historically obstructed by the Mahabharat hill range. In 1954, the then Royal Nepal Army completed the detailed design of the road from Kathmandu to Hetauda in the south of Nepal.[14] The road would connect with Birgung – the main trading point of Nepal with India – in the further south. However, the Army constructed 70 km of the road (Kanti Highway) out of 91 km by 1960. The road construction would not be complete over the next six decades.

In 1956, the Tribhuvan Highway was constructed with assistance from India by the Indian Army connecting Birgunj to Kathmandu.[15]

In the early eighties, traffic was increasingly diverted away from Tribhuvan Highway due to the steep incline that was difficult for engines to manage. However, the preferred flatter route from Birgunj via the East-West Highway and Prithvi Highway to Kathmandu was 92 km longer than the Tribhuvan Highway.

Over the decades, Nepal continued searching for the shortest and most convenient trade route with India. A Japanese study in 1991 proposed three corridors and a Swiss study in 1992 proposed five corridors. Also, in 1992, the UNDP sponsored a study on the Kathmandu-Hetauda-Birgunj corridor and identified a route along the Pharping Humane route as the optimal path to build the road upon. DANIDA supported study in 1993 proposed three tunnels and examined seven alternatives, which was followed by a Japanese study in 1994.

The Government of Nepal issued an invitation in 1996 for companies to express interest in undertaking or obtaining stakes in the Kathmandu-Terai Fast Track Road project under a build-own-operate-transfer (BOOT) model. However, there was no governing act in place, and as a result, the project stagnated completely for a decade while the country was ravaged under a decade-long Maoist insurgency.

2006-2015

After a decade of no movement, in 2006 the ADB revived the project with technical assistance to investigate feasibility of an investment program for North-South Fast Track Project[16] to improve the road linkage from Kathmandu to the East-West Highway of Nepal, which laid a basis for taking the Expressway forward. Under the project, final report on feasibility study and preliminary designs for the Fast Track was prepared by the Oriental Consultants in 2008.

During the early stages of the feasibility studies in May 2007, the alignment options for the Fast Track were assessed. A preferred alignment was chosen by the Government in October 2007 and Environmental Impact Assessment continued in parallel with the engineering feasibility study during 2008 under the ADB’s technical assistance.[17]

Based on the report of the feasibility and designs, the Kathmandu-Terai/Madhesh Fast Track Road Project office of the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport as per and the Government regulations and ADB policies/standards conducted an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for the Fast Track and submitted to the Ministry of Science, Technology and Environment by March 2015 (unofficial copy obtained). The ADB has not made the feasibility report available even to the media[18] while the EIA report is also not available publicly. The ADB project closed in 2010.

Even when the Fast Track was being studied, “there was significant objection” to taking productive agricultural land for the Fast Track Highway in Khokana as noted by the consultants in the EIA report[19]. As per the report, the alignment on the west bank of the Bagmati River has significant advantages that avoid valuable agricultural lands in Khokana.

Meanwhile, in 2006, the Government approved the Private Financing in Build and Operation of Infrastructures Act. As it intended to build the Fast Track under BOOT model with it only acquiring the land and entrusting the rest of the responsibilities to a concessionaire, it offered only to pay a toll-based concession in 2008, rather than fund the whole project. This offer was amended to include a grant of 15% of the capital costs in subsidies in 2012.

In 2014, the Government accepted an unsolicited proposal for the project from the Indian company named Infrastructure Leasing and Financial Service (IL&FS) that requested a minimum vehicle guarantee scheme on the Expressway. But subsequently, it re-advertised for bids for the project.[20]

In February 2015, the IL&FS won the bid for the Fast Track after the other two companies – Larson and Toubro Infrastructure Development Project, and Reliance Infrastructure – pulled out. It signed a memorandum of understanding with the Government while infrastructure and development experts began criticizing the deal as a financial risk. At the same time, following the 2015 magnitude earthquake, protests against Nepal’s new constitution in the southern plains blocked border points, which escalated into an undeclared blockade by India.

In October 2015, Nepal’s Supreme Court also ordered the deal to halt, citing concerns over national interest. A new Government cancelled all agreements with the IL&FS for construction of the Fast Track in 2016 and announced that it will construct the project by itself.[21]

2016

In March, land acquisition notice was published for the Project. Immediately, representative bodies of affected families of Khokana and Bungamati, including local political leaders, submitted a complaint to the Ministry of Home Affairs against the land acquisition, including regarding the absence of meaningful consultation with local communities regarding project design and impacts together with other projects proposed or planned in their areas.

On 26 September, the region filed a complaint with the National Human Rights Commission regarding the human rights violations in land acquisition for the highway. They demanded redress for violations of property, land and cultural rights that they have experienced, as well as a change in the alignment of the Fast Track as per the unofficial EIA report. Subsequently, various meetings and interactions of the community representatives with the local government representatives, concerned parliamentarians (including a parliamentary inquiry) and relevant Ministry and Nepali Army officials over the following years.

2017

On August 11, after years of delay due to uncertainty on the Project’s modality and financing, the Government decided to give the responsibility of construction management of the Fast Track to the Nepali Army that had earlier opened the track of the highway. Involvement of the Army in the project has led to insecurity and fear among Khokana locals opposing the project. It has also raised questions about the role of the Army in construction works vis-à-vis its influence in other sectors not related to security as well as corruption in the project with involvement of some high-level officials of the Army, which is above the anti-corruption laws of the country.[22]

The same year, then Prime Minister Prachanda foundation stone for the Fast Track was laid in Nijgadh. The IL&FS had already prepared the Detailed Project Report (DPR) for the Fast Track, but when the Army offered less than a third of their asked price of NPR 608 million (USD 5.8 million), it led to a fallout where IL&FS’s DPR was ultimately rejected. As a result, the IL&FS claimed NPR 2.37 billion in compensation for the preparation of the DPR from the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport since the agreement was that the company would not charge any amount for the DPR if it was awarded the contract to build the Fast Track.[23]

2018

In October 2018, the Nepali Army commissioned a South Korean company Soosung Engineering & Consulting Company to prepare a new DPR at the cost of NPR 70.45 million, which was approved on 19 August 2019.[24] However, the Army had begun construction of the Fast Track work even before preparation of the DPR. As per the DPR, the total length of the highway was reduced to 72.5 km from 76.2 km. The four-lane highway with 50 meters right of way will be 25 meters in the hills and 27 meters in the southern Terai plains. It will have 87 bridges. Similarly, three tunnels will be constructed at Mahadev Danda (3.355 km), Dhedre (1.630 km) and Lendanda (1.430 km) of Makwanpur district. At the same time, the project was estimated to cost NPR 175 billion, which is NPR 63.19 billion more than the earlier estimated of NPR 112 billion.

In the meantime, affected families and community representatives of Khokana and Bungamati together with rights activists organized protests rallies and demonstrations against the project. For example, in March, locals and activists protested for months outside the newly set up Army camp in Khokana that was installed forcibly on lands for which the landowners have not accepted any compensation.[25] In another protest the same month, they joined affected communities of other infrastructure construction, particularly illegitimate road widening across Kathmandu valley, against the government’s push for the Fast Track and other projects affecting their settlements that have cultural and historical importance and calling for removal of the Army from Khokana. At least six protestors were injured when police fired seven rounds of tear gas and used water cannon at the peaceful rally in capital Kathmandu.[26] International human rights organizations have voiced concerns against the violations of the rights of Khokana and Bungamati locals, including against the violent response in the peaceful protests.[27] In July, police also intervened in a protest in July in Bungamati near the project site with heavy force and with presence of Nepali Army officials[28] while the protests outside the army camp in Khokana have also run high with tension with locals fearful of armed military officials.[29] More protests were organized over the following months and years.[30]

Despite the numerous protests and notwithstanding the damages to crops and cultural sites, in December the Government announced that the FastTrack Expressway would follow the initially planned route.

Picture credit: Nepali Times

2019

On 28 August, The Government reportedly changed the alignment of the Fast Track to be closer to the east bank of the Bagmati River from its earlier plans and as they claimed to particularly safeguarding Sikali Temple in Khokana and Kodesh area, which hold cultural and historical significance . However, that will still impact the lands of hundreds of families, including communal and Guthi (religious trust) lands in Khokana and Bungamati. While great majority of the landowners had not accepted compensation to give up their land under the earlier notice, the Government published acquisition notice of additional 400 pieces of land mostly in Khokana and Bungamati (some in nearby Dukuchhap area) in December.[1] The alignment change resulted in acquisition of another 338 ropanis of land in Khokana area.[2]

Khokana, where the zero point of the Fast Track is proposed and the project faces the greatest opposition, is a small historical indigenous Newar town. Majority of the locals are farmers, and they utilize their spare time weaving, knitting and hand sewing while it is also widely known for its traditional mustard-oil seed industry.[3] Dependent on agriculture, the land is the most essential part of life and livelihood for Khokana locals. But Khokana stand to lose almost 60% of its fertile farmland and much of its heritage to the new infrastructure projects (map).[4] They will result in extreme difficulty for the people to survive as they will not be able to sustain their livelihood.

The Fast Track will run through Sikalichaur (open field off Sikali temple) where the annual Sikali Jatra festival is celebrated. That is unique to Khokana as the local do not celebrate Dashain (a major Hindu festival marked across Nepal) but mark Sikali Jatra – a five-day festival with masked dances for Goddess Rudrayani and other deities. The Fast Track will then go through Pingah, the funeral area, Ku Dey, Jugunti, Machaga Bagar, Chankhutirtha – all important parts of Khokana’s cultural circuit on the route to the next town of Bungamati.

Kudey is where the people of Khokana believe their ancestors first established the settlement—before moving up the ridge to its present location. Similarly, at Jugunti, the Jugi community of Newars will lose the cemetery where they have been burying their ancestors for generations. At Chankhu Tirtha, the expressway will go through the land where the final rites of the priests of Rato Machindranath – the deity of rain that has the longest chariot festival in Nepal – are performed.

People in Khokana have spiritual, social, cultural and economic connection with the land. At the same time, Khokana can be considered as one of the living museums of Nepal that recalls medieval time when the country was ruled by Malla kings.[5] It was once nominated as a world heritage site by UNESCO in 1996.[6] The whole settlement is filled with tangible and intangible heritage – many of which are historical and unique to the town. One example is a ritual conducted by Pujari Macha Guthi whereby eight young boys conduct a grand puja (ritual) of Goddess Sikali with puja material collected from all over the village which is known as “puja thawanegu” by the locals. During the ritual, nobody is allowed in or around the Sikali temple.

Also, at Ku Dey one of the archaeologically significant areas of Khokana as locals believe, there are sites where local perform various rituals – one of which requires the participants to wear a white long dress (jama and gamchhi). That is similar to ancient Kirat culture (one of the earliest eras of Nepal) suggesting a long-held connection of the place with historical Kirat, Lichhavi, Malla dynasties.

Contrary to the claim of locals, Nepal’s Department of Archaeology concluded that there was nothing of archaeological importance in Ku Dey. In October, the Department stated that if anything of archaeological value is excavated during construction of the Fast Track, it will be the responsibility of the constructor to preserve it.[7]

The locals thus themselves carried out preliminary excavation of the area in November and found many materials and remains with potential archaeological significance, including paved paths below the current ground level, clay water pipes alongside the road, a well, and other items, such as oil lamp, vessel, etc.[8] However, the Department of Archeology did not pay any attention to the repeated calls of local activists for preservation of the sites and further excavation as it is believed that the first settlement in Kathmandu valley started from this place.

Similarly, in Bungamati, the Fast Track will completely encroach upon the Kumari field (kumara khya). Every year, on the the night of the ninth day of Dashain festival, the victory festival of Goddess Vawani Devi is celebrated in the same field. That place is considered as the courtyard of the living goddess Kumari of Bungamati. Among historical, religious, cultural jatras and festivals of Bungamati, the jatra Bhawi Pith is celebrated on Paha Charhe i.e. the day before Ghode jatra. The Fast Track will disrupt the main route used for the jatra. Guthi lands of Parja khala, Bosi Khangi Guthi, Panejo Guthi and Vairav Guthi of that place will also be displaced. Like in Khokana, the cremation sites of Bungamati will also be impacted. Sources of drinking water and irrigation and agricultural lands of Guthi will be destroyed, which will end the Guthi tradition itself.

Further south, the Katuwal pond situated at Dukuchap, which is used to bring the holy bath water for the deity of Red Machindranath, will be buried. The Red Machindranath was brought to Nepal in Kaligat Sambat 3600. Machindranath was brought to Bungamati in the form of a bumblebee inside a Kalash (holy water vessel) from Katuwal pond by tantric methods. The chariot trip of Machindranath Jatra, known as the longest in the world, will be disrupted after the construction of the Fast Track. Other cultural places along its route will also disappear along.

Picture credit: Janasarokar Samiti

2020

On 12 February, representatives of the affected communities, and affected landowners in Khokana and Bungamati filed two writ petitions with the Supreme Court. The petitions stated that the projects being constructed would end the ancient civilization of both towns, and they called for the preservation of traditional settlements. The Court hearings on the case have been repeatedly delayed.

On 30 March, Save Nepa Valley movement and Nepal Sanskritik Punarjagaran Abhiyan mailed separate correspondences to the UNESCO, ILO and the UN Country Office in Nepal calling for their urgent attention to the project. The letters contained reference to the serious threats of displacement faced by Newar communities, violations of their lands and resources, and destruction of cultural heritage. They called for the UN bodies to seriously consider these matters, and to draw the attention of the Government of Nepal regarding threats to World Heritage Sites in Khokana, and furthermore for timely and decisive action before irreversible harm is caused.

In July, Janasarokar Samiti of Khokana and Bungamati – the official representative bodies of the affected families and communities organized ‘paddy transplantation protest’ in Kokhana at the proposed entry point of the Fast Track. Rights activists from across Kathmandu valley participated in the protest after police suppressed earlier similar protest by the locals in June. While the protestors peacefully demanded to be allowed to cultivate the fields at the entry point area, clashes ensued when heavy police and armed police forces deployed tried to brutally suppress the protest. Over a dozen protestors were injured when police lobbed tear gas shells and charged batons while four police personnel were also injured.[9]

On 12 September, the locals again confronted the police again when the project began constructing a bridge in the nighttime at the zero point of the Fast Track amidst prohibitory orders for the general public to stay indoors due to Covid-19 pandemic. Angry locals also dismantled the structures set up for the construction.[10]

On 9 July, CEMSOJ, the Himalayan Human Rights Monitors (HimRights), and Save Nepa Valley movement filed a joint submission for the 3rd Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of Nepal, including information about the human rights challenges faced by communities in Khokana and Bungamati due to Fast Track and other projects.

On 1 December, Janasarokar Samiti of Khokana and Bungamati called on two UN experts in Geneva to take prompt action for safeguarding their rights against threats of displacement and violations of their land, resource and cultural rights due to the Fast Track and other ill-planned projects. The UN Special Rapporteurs on the rights if indigenous peoples and the field of cultural fights were urged to jointly examine the information, and correspond with the Government of Nepal to protect and promote indigenous rights. The UN experts were requested to write to the Government of Nepal to halt the construction of the Fast Track Expressway, and revise its alignment, remove the Nepal Army camps assigned to construct the expressway, and restore the lands to its original owners. They were also requested to demand the right to peaceful assembly and freedom of expression, and the obtaining of FPIC of project affected locals.

2021

On 15 March, the shadows of corruption started haunting the project. The parliamentary Public Accounts Committee (PAC) began considering an investigation into the second phase contract awarding process for the construction of the Kathmandu-Tarai Fast Track by Nepali Army. The parliamentary committee sought to carry out the investigation on suspicion of possible corruption while awarding the contract. The Army has been accused of making its own procedures to award the contract to two Chinese companies, namely Poly Chhangda Engineering Company Limited and China State Construction Engineering Corporation Limited.

On 30 March, the Working Group on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises, and the Special Rapporteurs on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living, on the situation of human rights defenders, and of the rights of indigenous peoples of the UN, sent a letter to the Government of Nepal regarding allegations of human rights violations against indigenous Newa communities in Khokana and Bungamati as a result of the construction of the Kathmandu – Terai/Madhesh FastTrack Expressway project. It explicitly drew attention to the delayed administrative and judicial procedures, and the effects that had on indigenous rights, especially as construction has continued in the face of these delays. The UN bodies further expressed concerns that FPIC had not been sought for the project. They requested information from the Government of Nepal regarding any meaningful consultation sought from Newar Indigenous Communities, as well as the status of any litigation processes before the Supreme Court of Nepal.

In April, the PAC requested the Government to halt the contract and the works until the Nepali Army would ensure transparency in the bidding process. However, both the Government and the Nepali Army did not give much weight to PAC’s opinions, first ignoring them, and then proceeding on their own terms by awarding the contracts to Poly Changda Engineering Company and China State Construction Engineering Corporation on 16 May.

In the meantime, the progress of the project stagnated. Due to recurring controversies and delays, the project’s original cost estimate of Rs56 billion had doubled to Rs112 billion in seven years, and the Army, which had initially set August 2021 as a completion deadline for the project, extended it to July 2024. The letter sent to the Government of Nepal by the UN bodies required that the government of Nepal responded to their concern and requests for information within 60 days. However, by May 30, the time frame had lapsed, and the Government of Nepal had not responded.

2022

On 25 March, national media reported that the contracting companies were not respecting the environmental mitigation measures prescribed by the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), especially with regard to tree cutting activities – which resulted in increased geological instability and higher possibility of landslides in inhabited areas. Pollution represents another problem during the construction phase, and local residents have repeatedly denounced the disruption to their peaceful lives brought by the project construction companies, which did not implement mitigation practices. Last but not least, the Army has ignored the mandatory installation of wastewater treatment plants at project sites. Despite all these violations, the Nepali Army kept reaffirming its compliance with the EIA provisions.

On 10 July, as part of their annual paddy plantation protest, Indigenous Newar communities in Khokana and Bungamati, through a public statement, called on the same UN mechanisms in Geneva to take follow up actions for safeguarding their human rights. They also kept denouncing violations of their rights with the media, alleging breaches of international law on behalf of the Government, and reaffirming that ‘the roads can be both a boon and a bane’. In the meantime, the progress of the project kept being ‘sluggish’, with consequences on the credibility of the Nepali Army as project implementation agency, despite the latter’s claims that construction works would speed up and the project would be completed on time.

Towards the end of 2022, the Government of Nepal reportedly formed a committee to provide suggestions regarding the issues around Fast Track Expressway, which submitted its report to the Prime Minister in February 2023 – but that is not available publicly.

2023

On 18 April 2023, the Government, through a decision of the Cabinet of Ministers (dated BS 2080 Baishakh 5), formed a high-level committee with the Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister as the Coordinator to resolve the land acquisition issues in Khokana area under the Fast Track Expressway. Through another cabinet-level decision on 1 August (BS 2080 Shrawan 16), the term of the Committee was extended by three more months.[11]

On 24 August, Lalitpur Metropolitan City organized a public interaction in Khokana to solicit advice and suggestions from the locals on resolving the land issues for the Fast Track Expressway as requested by the high-level committee. Khokana and Bungamati locals who spoke at the interaction overwhelmingly rejected construction of the Expressway in their lands and called for moving the entry point to further south in Dukuchhap.[12] Accordingly, the Metropolitan City informed the Committee on 3 October (BS 2080 Kartik 3).

Also, in August, three more packages of construction work were awarded by the project, the revised DPR reduced the length of the road. Yet, demands of the communities in Khokana and Bungamati to re-route the Fast Track were not addressed.

The following are major companies are currently involved in the project:

- Yooshin Joint Venture (Joint Venture of Yooshin Engineering Corporation, Korea Expressway Corporation and Pyunghwa Engineering Consultants Ltd. of South Korea in association with Garima International Design Associates Nepal Pvt. Ltd. and SITARA Consult Pvt. Ltd of Nepal) is the international consultant for project design and construction supervision for completing the project construction with quality – agreement signed by the Project with the joint venture on 15 May 2020.

- M/S China State Construction Engineering Corp. Ltd (China) has signed a contract package with the Project for 3,355-meter Mahadevtar tunnel section (contract date 14 May 2021; scheduled completion date – 14 Dec 2024)

- M/S Poly Changda Engineering Co. Ltd. (China) signed a contract package for 3,060-meter Dhedre and Lendanda tunnel sections. (contract date 14 May 2021: completion date 14 Dec 2024)

Additionally, following companies/joint ventures have been contracted for construction of various sections of the Expressway, including bridges.

- China First Highway Engineering Co. Ltd., China – contract date: 10 Jan 2023; completion date – 730 days from commencement date

- Xingrun-Ashish-Tundi JV, Lalitpur, Nepal – contract date: 15 Nov 2022; completion within 730 days from commencement (9 Dec 2024)

- Kumar-Roshan-Sichuan JV, Mahendranagar, Nepal – contract date: 17 Jan 2022; completion within 1,000 days (26 Oct 2024)

- CAMCE-SDLQ JV, China – contract date: 21 Feb 2022; completion within 970 days (2 Dec 2024)

- Poly Changda Engineering Co. Ltd., China – contract date: 21 Feb 2022; completion within 970 days (2 Nov 2024)

Meanwhile, the project cost has kept increasing, which has reached Rs 213 billion.

In December, Nepal Army Chief Prabhu Ram Sharma said that the highway might not be ready even in three and a half years.

Nepal’s Supreme Court hearings on the petitions filed by the affected communities have been repeatedly deferred.

An estimated 26% of the project has been completed by 2023. The delays have partially been due to consistent local protests of communities in Khokana and Bungamati, which have resulted that the contract for the construction package in those areas have also not been awarded.

2024

On 25 June, the UN’s four Special procedures – the Working Group on Business and Human Rights, and the Special Rapporteurs in the field of cultural rights, on the right to adequate housing, and on the rights of Indigenous Peoples, sent follow up letters to the Governments of Nepal, Republic of Korea (South Korea) and China; Asian Development Bank (ADB); and the businesses involved – Soosung Engineering and Consulting Co. Ltd., Yooshin Engineering Corporation, Korea Expressway Corporation and Pyunghwa Engineering Consultants Ltd. of South Korea; China State Construction Engineering Corp., Poly Changda Engineering Co. Ltd., China First Highway Engineering Co. Ltd., China CAMC Engineering Co. Ltd. (CAMCE), Sichuan Road and Bridge (Group) Co. Ltd (SDLQ), and Xingrun Construction Group Co. Ltd. of China; and Garima International Design Associates Nepal Pvt. Ltd., SITARA Consult Pvt. Ltd., Ashish Nirman Sewa Pvt. Ltd., Tundi Group, Kumar Shrestha Nirman Sewa, and Roshan Construction Pvt. Ltd. of Nepal.

Among them, only the Government of Republic of Korea and the Soosung Engineering and Consulting Co. Ltd. responded to the UN Special Procedures on 19 and 23 August respectively. The South Korean government provided only general response about the Guidelines on Business and Human Rights a National Action Plan for the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights it had adopted and been implementing – nothing specific to the Fast Track Expressway. It also informed that individuals adversely affected by South Korean businesses may file suit in the South Korean courts pursuant to the Act on Private International Law. In its response, Soosung Engineering & Consulting informed that it had limited scope of work in 2018 under the contract with the Nepali Army for updating the feasibility study and preliminary design of the Fast Track Expressway conducted by the ADB in May 2008. Despite their maximum efforts to choose best alignment to reduce adverse impact in social and cultural life of Khokana locals, it was unduly restrictive for them to update previous works done by the ADB.

On 28 June, Federal Parliament member Udaya Shumsher Rana informed the Lower House of Parliament that the locals in Dukuchhap in Godawari municipality (ward no. 8) have agreed to having the entry point of the Fast Track Expressway in their lands if needed. He also called on the Government to provide information about the works of the Committee formed under the Defense Ministry.[13]

On 27 October, Federal Parliament members from Khokana and Dukuchhap and local government representatives proposed moving the entry point of the Fast Track Expressway from Khokana to Dukuchhap at a consultation organized by the high-level committee.[14]

[1] https://www.facebook.com/arbu007/posts/4079175582099923

[2] https://pressreader.com/article/281526522750099, https://myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com/news/alignment-change-in-fast-track-historical-khokana-to-be-preserved/

[3] https://honeyguideapps.com/blog/khokana-nepal

[4] https://www.nepalitimes.com/banner/our-land-is-us-we-are-our-land/

[5] https://www.nepalmtlovers.com/khokana-village-tour.html

[6] https://whc.unesco.org/en/statesparties/np

[7]https://kathmandupost.com/miscellaneous/2018/12/14/expressway-to-stay-on-course-despite-khokana-protests

[8] https://rukshanakapali.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Khokana-report.pdf

[9] https://kathmandupost.com/visual-stories/2020/07/04/four-policemen-injured-in-clash-with-locals-in-khokana

[10] https://pahilopost.com/content/20200912162952.html (in Nepali)

[11] https://nawakantipur.com/archives/160049 (in Nepali)

[12] https://onlinemajdoor.com/?p=97197&fbclid=IwY2xjawHWEOVleHRuA2FlbQIxMQABHc6GcsXzyOgiL4WSqcAiLjFY0VmDD1XmDU0Dv_8iAaSYNggD9ZPmiSo72g_aem_Y27kxbAxCSTPsWKK8_ZxCw (in Nepali)

[13] https://www.facebook.com/RanaUdayaShumsher/videos/830196392539853

[14] https://www.facebook.com/RanaUdayaShumsher/posts/pfbid0Js81Vf99aPLYLpaBg2MJ7uZTJaDpkeTsettibg4yEYq1Ua5C62AyrNrEsGkTkgBwl, https://www.facebook.com/Ootsheekafyu/videos/1568786337360041